Notes & Commentary

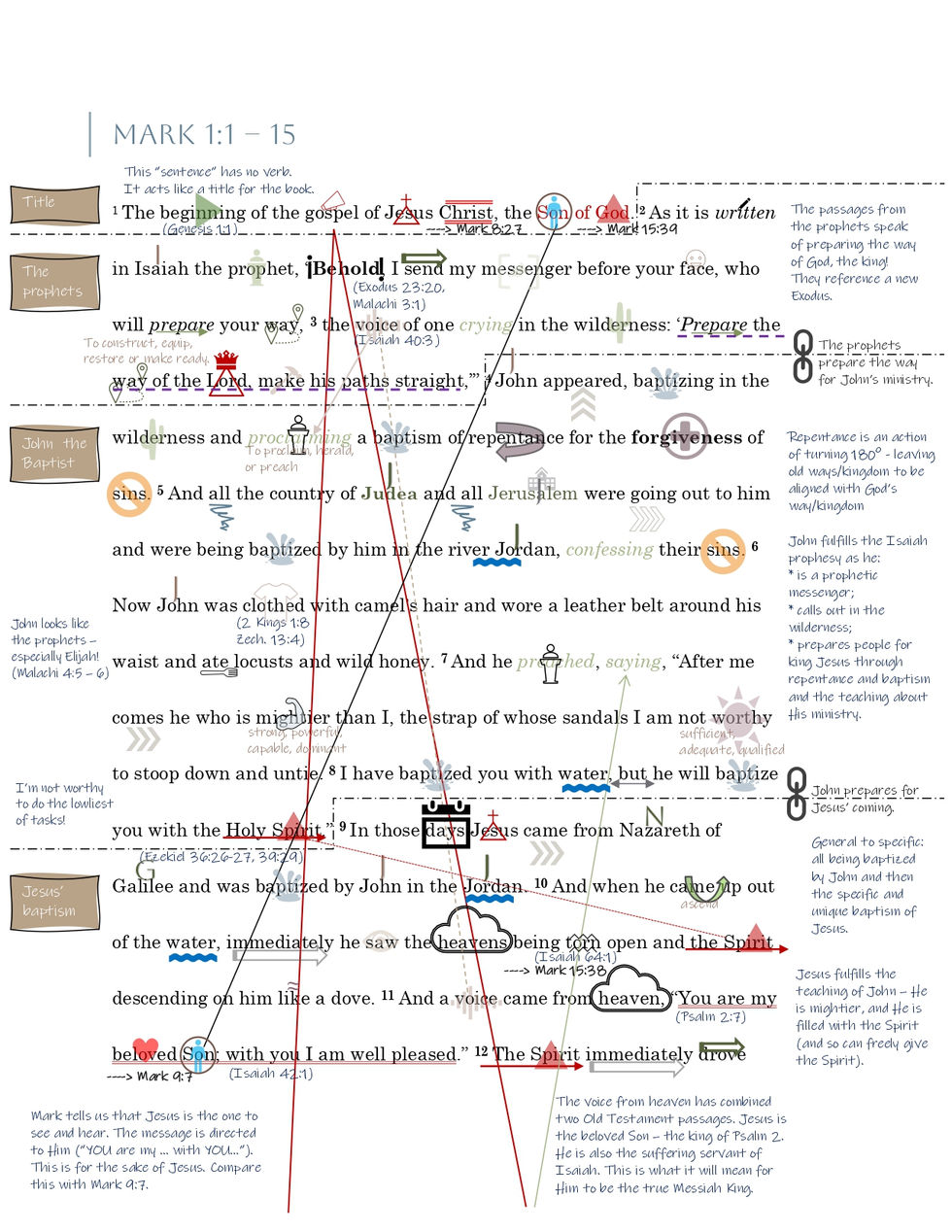

Mark 1:1 - 15

¶1: Title (1:1)

Holman Bible Atlas maps

Holman Bible Atlas maps

The term “beginning” is often associated with the commencement of a king’s reign (for example, Jeremiah 26:1). The language also evokes Genesis 1 and the very beginning of history, where God creates the world and establishes His rule, giving the term ‘beginning’ strong creation and kingdom associations.

The word “gospel” is a Greek term meaning “good news.” In the ancient world it commonly referred to an announcement delivered by a herald, such as news of a military victory, the birth of an emperor, or the accession of an emperor to the throne. In the Old Testament, the prophets use this language to describe God’s saving action and end-time deliverance (Isaiah 40:9; 52:7; Nahum 1:15).

The name “Jesus” is the Greek form of the Hebrew name Joshua, meaning “Yahweh is salvation.”

The title “Christ” is the Greek translation of the Hebrew word Messiah, meaning “Anointed One.” In the Old Testament, anointing is associated primarily with kings and priests. Israel’s Scriptures express a strong hope that a descendant of David would one day rule again when God restored His kingdom to His people. The expected Messiah was understood as one chosen and empowered by God, appointed to redeem His people, judge His enemies, and exercise dominion over the nations. In the first century, many Jews expected the Messiah to act as a political or military deliverer who would overthrow Roman rule and establish a physical kingdom for Israel. Various messianic claimants arose in this period, but all were ultimately defeated by Rome (see Isaiah 7–11; the Servant Songs in Isaiah 40–55; and royal psalms such as 2, 45, 72, 89, and 110).

The phrase “Son of God” is rooted first in God’s identification of Israel as His “son” (Exodus 4:22–23; Hosea 11:1), a relational image that portrays God as creator, protector, and provider of His people. Later, this language is taken up in Israel’s royal theology, where David and his descendants are given a unique status of sonship (2 Samuel 7:14; Psalm 2). In this context, “son of God” became closely associated with the role of the king, one who ruled on God’s behalf. Similar ideas were present throughout the ancient Near Eastern world, where rulers often claimed to be sons of the gods, presenting themselves as divinely authorized representatives and rulers.

Commentary

The opening verse of Mark functions as the title of the book and immediately introduces its central focus: the gospel of Jesus. This gospel is both the good news proclaimed by Jesus and the good news about who Jesus is. The word “gospel” comes from the Greek term for “good news” and was commonly used in the ancient world to announce military victory or the accession of a ruler. Mark’s Gospel proclaims God’s decisive victory and the arrival of His kingdom through Jesus.

Mark describes this as “the beginning of the gospel of Jesus.” The language deliberately echoes the opening of Genesis, where God begins His work of creation and establishes His rule. In the same way, Mark presents the ministry of Jesus as the beginning of a new creative act of God—the restoration of His kingdom in the world. At the same time, this beginning points forward. God’s creative work and kingdom begun in Jesus continue to unfold through the lives of Christ’s Spirit-filled followers. In this sense, the gospel is not merely a set of beliefs or teachings; it is centered on a person—Jesus Himself. This emphasis on “beginning” may help explain the Gospel’s abrupt ending, which leaves the story open and unfinished.

From this title, Mark introduces two defining truths about Jesus. First, He is the Christ—the anointed one promised in Israel’s Scriptures, the King in the line of David through whom God would establish His rule and bring salvation to His people. In Jesus’ day, expectations about the Messiah varied widely, often emphasizing political or military deliverance. Mark therefore delays using the title “Christ” again until chapter 8, allowing Jesus’ actions and teaching to reshape what it truly means to be God’s anointed king.

Second, Jesus is the Son of God. This title points to His unique relationship with God and His role as God’s true representative and ruler. In the Roman world, emperors were often called “sons of the gods,” claiming divine authority. Mark’s opening declaration quietly but decisively challenges these claims: Jesus, not Caesar, is the true Son and rightful King. These two titles—Christ and Son of God—frame the Gospel. The first half culminates in Peter’s confession that Jesus is the Christ (8:27), while the second half reaches its climax when a Gentile Roman centurion at the cross declares that Jesus is the Son of God (15:39).

From the very first verse, Mark announces that this gospel is a proclamation of victory. As readers, we are invited to watch closely as the theme unfolds, asking: Who is Jesus? What does it truly mean for Him to be the Christ and the Son of God? What kind of kingdom does He bring? And why is this message genuinely good news?

¶2: The Prophets (1:2 – 3)

Michelangelo

Mt. Quruntul, traditional site of Christ's temptation

Michelangelo

Mark begins by writing, “as it is written in Isaiah,” yet the quotation that follows combines passages from Isaiah, Malachi, and Exodus. This reflects an accepted Jewish literary practice often called conflation, in which multiple texts sharing a common theme are cited together. Isaiah is named explicitly because his prophetic vision plays a central role in shaping how Mark presents the ministry of Jesus throughout the Gospel. In addition, the quotation from Isaiah is the longest and most prominent element in this opening citation.

The first portion of the quotation draws from Exodus 23:20 and Malachi 3:1, both of which speak of God sending a messenger to prepare the way before Him. In Exodus 23:20, the messenger is sent ahead of Israel to lead them safely into the promised land, driving out their enemies and requiring the people’s obedience. In Malachi 3:1, the messenger prepares for the Lord’s return to His holy temple. This promise is especially significant because God’s presence had departed from the temple during the exile, yet the prophets anticipated a future day when He would return to dwell again among His people (for example, Ezekiel 43:2–4). In Malachi, the messenger calls Israel back to covenant faithfulness and repentance in preparation for the Lord’s coming. Later in the book (Malachi 4:5–6), this figure is associated with an Elijah-like prophet, and the Lord’s arrival is portrayed as a time of judgment and purification.

Mark then cites Isaiah 40:3, a verse drawn from a larger passage of comfort and good news for God’s people. Isaiah describes the Lord’s coming using vivid imagery: God is pictured as traveling to Jerusalem along a road through the wilderness. The people are called to prepare the way for Him as they would for a royal visit—clearing obstacles and making the path straight. When the Lord comes, Isaiah declares, His glory will be revealed and witnessed by all people on earth. This imagery evokes a new Exodus, in which God once again leads His people into restored life and blessing.

In Scripture, the term “wilderness” does not refer only to barren desert terrain but also to uncultivated pasturelands suitable for grazing. The wilderness carries deep symbolic weight in Israel’s story. It was there that God redeemed His people from slavery, revealed His law, and established His covenant during the Exodus. It was also a place of testing, where Israel spent forty years before entering the promised land. Because of these formative experiences, the wilderness became associated with God’s preparation of His people for His purposes. Many prophets therefore envisioned a future act of salvation—a new Exodus—emerging from the wilderness (see Exodus 16; Numbers 14; Deuteronomy 1–2, 8; Isaiah 40:1–5; Ezekiel 20:35–38). In the wider biblical story, the wilderness is also linked with the conditions of creation itself. Genesis describes the pre-creation world as “formless and void” before God brings order and life through His word (Genesis 1:2). This imagery contributes to the wilderness being understood not only as a place of testing, but also as a setting where God acts decisively to bring renewal, order, and life.

Commentary

Mark opens the Gospel with a carefully woven set of quotations from the Old Testament. In their original contexts, these texts speak of God providing servants who prepare and lead His people—both in Israel’s past, as they were led into the promised land, and in the future, as God Himself would come to meet His people in the land once more.

By beginning the “beginning of the gospel” with these Scriptural citations, Mark makes several important claims. First, the gospel of Jesus is firmly rooted in God’s saving work throughout history and bound to all of His promises to Israel. Mark’s use of passages drawn from the Law and Prophets highlights that the whole of Scripture bears witness to this gospel. Jesus is not an afterthought or a departure from Israel’s story, but its fulfillment—the culmination of all that God had been preparing His people for all along. Significantly, these texts share the Exodus as a common theme, Israel’s great act of salvation. Mark presents the work of Jesus as a new and greater Exodus, in which God once again leads His people into the promised land of His kingdom, where they will truly know Him.

These quotations also prepare the reader for God’s coming and work. They emphasize that God’s saving action requires preparation—a readiness shaped by awareness, repentance, and obedience. Mark understands these prophecies to be fulfilled in the ministries of both John the Baptist and Jesus. These verses prepare the reader for their coming, situate them within God’s story, and interpret their lives and ministries. John appears as an Elijah-like figure who goes before the Lord, calling out in the wilderness and preparing the people for the Day of the Lord and the arrival of God’s kingdom. Jesus is identified as the Lord and King who comes to His people, whose glory will be revealed to all. Notably, the pronouns that once referred to God in these texts are now fulfilled in Jesus, the Christ and Son of God. His coming is so momentous that it demands preparation.

Mark’s emphasis on Isaiah is especially significant. Throughout the Gospel, Isaiah’s language and imagery shape how Jesus’ identity and mission are understood. Paying attention to these Isaianic echoes will therefore be essential for interpreting Mark’s message, as they reveal how Jesus fulfills the deepest hopes and longings expressed in Isaiah’s prophecies—most significantly that Jesus is the suffering servant through whom God’s kingdom comes, bringing salvation and rest to people throughout the world.

¶3: John the Baptist (1:4 – 8)

The traditional site of John's baptisms

Tissot

The traditional site of John's baptisms

The practice of baptism was rooted in the ceremonial washings of the Old Testament and the wider ancient world, which symbolized the removal of impurity in preparation for entering a sacred space. By the time of Jesus, Judaism had developed extensive traditions around such washings, with some groups—such as the Pharisees—being especially meticulous. Baptism, however, was distinct from these repeated rituals. It was typically a one-time act involving full immersion, marking a decisive transition. In John’s time, baptism was most commonly associated with Gentiles converting to Judaism, symbolizing a complete break from their former way of life and entry into the covenant people of God. In Israel’s Scriptures, water crossings such as the Red Sea and the Jordan River were associated with deliverance from slavery and entry into the promised land, associations that would have shaped how baptism was understood. For Jewish individuals to submit to baptism was therefore striking, as it implied the need for repentance and renewal rather than reliance on ancestral identity as sufficient for covenant standing.

Repentance in Scripture goes beyond a mere “change of mind.” It reflects the Old Testament concept of turning—a reorientation of one’s life away from sin and back toward God. This language is frequently used by the prophets to describe returning to covenant faithfulness and renewed trust in the Lord (see 1 Kings 8:47; Isaiah 30:15; 59:20; Jeremiah 15:19; Ezekiel 14:6; 18:32).

The biblical language for sin conveys ideas such as missing the intended path, deviating from what is right, or breaking a relationship of trust. Sin can also be described as rebellion against God’s authority. In the Old Testament, sin required atonement, and forgiveness was understood to be something only God could grant, mediated through the sacrificial system centered on the temple (see Leviticus 26:40–42; Deuteronomy 30:11–20; Psalm 51; Isaiah 59:1–2).

Forgiveness in the Old Testament is often expressed through imagery of removal or lifting away. Forgiveness was closely tied to atonement and sacrificial practices, particularly on the Day of Atonement, when Israel reflected on God’s mercy and His continued dwelling among His people. According to the Law, priests could pronounce forgiveness in connection with repentance, restitution, and sacrifice (see Exodus 34:6–7; Leviticus 17:11; Nehemiah 9:17; Psalm 103:12; Isaiah 53; Jeremiah 31:34; Daniel 9:9; Micah 7:18–19).

The Jordan River is a narrow, winding river that flows below sea level through the land of Israel. While it had limited importance for irrigation, it held deep symbolic significance in Israel’s story of salvation. It was the boundary Israel crossed to enter the promised land after the wilderness, and it was closely associated with prophetic activity, particularly in the ministries of Elijah and Elisha (see Joshua 3–4; 1 Kings 17; 2 Kings 2; 2 Kings 5).

Jerusalem was the religious and symbolic center of Jewish life. Situated in the hills of Judah, it was home to the temple, understood as the place where God chose to dwell among His people. During the first century, the city had a population of roughly 30,000 and functioned as the heart of Israel’s worship, identity, and hope.

John the Baptist’s clothing of camel’s hair and a leather belt reflects the traditional appearance of Israel’s prophets, most notably Elijah (2 Kings 1:8; Zechariah 13:4). His clothing and lifestyle signaled continuity with the prophetic tradition and aligned him with the prophetic tradition associated with calling the people to repentance in anticipation of God’s coming. John’s diet of locusts and wild honey was both ritually permissible (Leviticus 11:22) and practical for life in the wilderness, reflecting a life of simplicity and separation from ordinary social patterns.

In the ancient world, removing another person’s sandals was a task typically assigned to a slave. Some Jewish teachers even regarded this duty as too menial for a Hebrew servant. John’s statement that he was unworthy to untie the sandals of the one coming after him reflects a widely understood cultural image of humility and subordination.

The prophets had long spoken of a future outpouring of God’s Spirit, associated with renewal, cleansing, and restored obedience (Ezekiel 36:26–27; 39:29; Joel 2:28–32). This hope involved God giving His people new hearts and empowering them to live faithfully in covenant relationship with Him.

Commentary

John prepares the people by calling them to be baptized in the Jordan River as an act of repentance for the forgiveness of sins. At the time, baptism was a cleansing ritual typically practiced by non-Jews who wished to convert to Judaism. John’s message was therefore radical: all people, regardless of heritage or religious background, were spiritually unclean and in need of renewal before God. This renewal required repentance—a decisive turning away from their former ways of life—and was symbolized through baptism as a public act of commitment to follow God. Through this repentance, the people were being prepared to receive God’s forgiveness.

The choice of the Jordan River is especially significant. Israel had first entered the promised land by crossing the Jordan, leaving the wilderness behind and stepping into God’s promise. Now, John calls the people to enter the Jordan once again, symbolizing the need for a fresh beginning. To pass through the Jordan in repentance was to acknowledge that, despite living in the land, God’s people still stood in need of renewal—they were, in effect, in a spiritual wilderness. Entry into God’s promised future would once again require repentance, humility, and trust in God’s saving action.

The location of John’s ministry deepens this meaning. The wilderness and the Jordan were places where God had previously saved His people and where the prophets promised He would act again. John’s clothing evokes the memory of Elijah, the prophet expected to come before the Day of the Lord. This connection helps explain why so many people were drawn to him. The arrival of an Elijah-like figure signaled that God’s kingdom and judgment were imminent, and many wanted to be spiritually clean and ready for this moment. John’s simple clothing and diet also reflected his complete devotion to God’s purposes and his dependence on God’s provision rather than religious status or power.

John’s message, which accompanied his baptism, was that a stronger one—the Messiah—was coming after him. John understood his role as preparatory: he was to ready the people for the arrival of this greater figure. The Messiah’s superiority was so great that John did not consider himself worthy even to perform the lowest task of a servant for Him. While John’s baptism pointed to outward cleansing and preparation, the Messiah would bring an inward and lasting transformation. He would baptize with the Holy Spirit, fulfilling God’s promises of a new covenant. Through the gift of the Spirit, God’s people would receive new hearts and be enabled to live in faithful obedience. In this sense, the promised gift of the Spirit is itself the fulfillment of God’s promise of life within His kingdom—a new and living reality where God dwells with His people.

From the beginning, Mark presents the gospel as the story of a new creation. Repentance is the means by which God prepares His people for this new work, forming a renewed community in which His Holy Spirit dwells and through whom His kingdom is made known in the world.

¶4: Jesus' Baptism (1:9 – 13)

Open.Bible maps

Open.Bible maps

Nazareth was a small and largely insignificant village in the region of Galilee. It is never mentioned in the Old Testament, the Jewish Talmud, or the writings of Josephus, suggesting it held little cultural or religious importance. It is likely that many people in Jerusalem had never heard of Nazareth at all. Scholars estimate that the population of the village at the time of Jesus may have been as small as a few hundred people.

The “tearing of the heavens” echoes the language of Isaiah 64:1, where the prophet pleads for God to come down in power, reveal Himself, and bring salvation to His people. Although Israel had returned from exile, there remained a deep longing for renewal and for a decisive act of God’s presence. Mark uses vivid imagery to describe this moment. Notably, the verb translated “tear” appears only twice in Mark’s Gospel—here and later when the temple veil is torn in two at Jesus’ death. In Jewish thought, the temple was understood as a symbolic meeting point between heaven and earth, associated with God’s dwelling among His people.

The voice from heaven brings together language and imagery from two key Old Testament passages. The first is Psalm 2:7, a royal psalm used in the coronation of Israel’s kings, affirming God’s covenant commitment to the Davidic ruler. The second is Isaiah 42:1, which introduces the figure of the servant whom God upholds and delights in, upon whom He places His Spirit. In Isaiah, this suffering servant is called to bring justice and restoration, not only to Israel but to the nations. Together, these passages provided key categories within Israel’s Scriptures for describing God’s chosen and commissioned figure: a royal anointed one and a servant who suffers on behalf of others.

The number forty frequently marks periods of testing, preparation, or transition in the biblical story of salvation. Examples include the forty days of rain during the flood, Moses’ forty days on Mount Sinai, and Israel’s forty years in the wilderness prior to entering the promised land. Such periods often precede a new stage in God’s redemptive work.

Commentary

Jesus comes from Nazareth, an obscure village in the region of Galilee. By submitting to baptism at the hands of John, Jesus publicly aligns Himself with God’s saving work and identifies with the people He has come to redeem. Though He is the stronger one John proclaimed, Jesus does not stand apart from those preparing for God’s kingdom. Instead, He enters fully into their story. This act marks the beginning of His public ministry and confirms His role as God’s anointed one, as He is filled with the Holy Spirit.

The tearing open of the heavens is a striking image, signaling that the barrier between heaven and earth has been decisively breached. God’s kingdom is breaking in as He answers Isaiah’s prayer (64:1) that the heavens would be torn open and God would come to dwell with His people once again. Mark later echoes this moment when the temple veil is torn at Jesus’ death, reinforcing the idea that God is now acting in a new and direct way among His people. At Jesus’ baptism, God’s Spirit descends upon Him, affirming His identity as the beloved Son and confirming that God’s saving presence is now at work through Him.

The Spirit descends like a dove, evoking imagery associated with peace and new creation. Just as God’s Spirit hovered over the waters at the beginning of creation, and just as the dove signaled new life after the flood, Jesus’ baptism marks the beginning of God’s recreation project in the world. Empowered by the Spirit (Isaiah 11:1–5), Jesus begins His mission of restoration, forgiveness, and proclamation of God’s kingdom—a mission that will unfold through His teaching, actions, suffering, and victory throughout the rest of the Gospel.

God’s voice from heaven declares Jesus to be His Son, drawing together allusions from Psalm 2 and Isaiah 42. These texts unite royal kingship with suffering service in a way that was unexpected and deeply challenging—an issue that will later become a central stumbling block for Jesus’ own disciples. This moment functions as both a coronation and a commissioning. Jesus is revealed as God’s chosen king, yet His mission will unfold in the way of faithful obedience and suffering service. This is what it means for Him to be the Christ. His authority and calling come from God Himself, not from human recognition or power.

Immediately, the Spirit drives Jesus into the wilderness. Being led by the Spirit does not remove Jesus from trial; it leads Him directly into it. In the wilderness, Jesus confronts Satan and remains faithful, succeeding where both Adam and Israel had failed in the wilderness. The mention of wild beasts underscores the danger of the setting, a detail that would have resonated with Mark’s audience, many of whom lived under the threat of persecution. Yet even here, God’s presence sustains Jesus. The wilderness and beast imagery also recalls humanity’s earliest story, when creation was meant to be ordered under God’s rule rather than threatened by chaos. In contrast to Adam, Jesus remains faithful, signaling that God’s work of restoring creation has begun.

The wilderness thus becomes the setting for the beginning of the new Exodus foretold by Isaiah and the prophets. After forty days—a period associated throughout Scripture with testing and preparation—Jesus emerges ready to begin His public ministry. Having faced temptation and remained faithful, He stands prepared to lead God’s people out of the wilderness and into the life of God’s kingdom.

¶5: The Kingdom of God is Here (1:14 – 15)

The word “time” in Jesus’ proclamation does not refer simply to chronological time but to a decisive moment or season within God’s purposes. In the Old Testament and Jewish thought, this language was often used to speak of moments when God acts in a climactic way within history. The prophets anticipated a future time when God would intervene decisively to bring restoration, judgment, and renewal. Jesus’ announcement draws on this expectation, signaling that a long-awaited moment in God’s redemptive plan has arrived.

The phrase “kingdom of God” does not appear explicitly in the Old Testament, yet the concept runs throughout Israel’s Scriptures. God is portrayed as king from the opening chapters of Genesis, where humanity is created to live under His rule and blessing. This ordered relationship is disrupted by sin, but the Old Testament continues to point toward God’s intention to restore His reign among His people. The promised land and the temple function as partial and provisional expressions of God’s rule and presence. The prophets looked ahead to a future in which God would reign without rival, idolatry would be removed, and the nations would be drawn into the worship of the one true God. Within these hopes, the coming Messiah was closely associated with the restoration and establishment of God’s kingdom.

Commentary

With these verses, Jesus’ public ministry begins, and Mark provides a concise summary of the message Jesus proclaims throughout the Gospel. What John the Baptist prepared the people for is now taking place. Jesus appears, announcing that the decisive moment in God’s saving purposes has arrived.

John’s ministry has fulfilled its role. His imprisonment signals a turning point in the story: the time of preparation has given way to the time of fulfillment. John proclaimed that one was coming who would bring God’s Spirit; Jesus now announces that this promised moment has arrived. The contrast between their messages is intentional. John pointed forward; Jesus declares that what was anticipated is now present.

Jesus’ central announcement is that the kingdom of God has come near. Throughout Scripture, God’s kingdom refers to God’s reign—His active rule in which creation lives in harmony under His wisdom, authority, and life-giving presence. Under His reign, humanity lives unencumbered by sin and death. Though humanity was created for this life with God—pictured first in a garden—sin brought rupture and exile. Jesus proclaims that God is now acting to restore what was lost. God’s reign is breaking into the world in a new and decisive way.

Jesus’ message is truly good news, and it is simple and urgent: the proper response to the arrival of God’s kingdom is repentance and belief. Repentance involves turning away from old allegiances and patterns of life shaped by the kingdoms of this world. Belief is not mere intellectual agreement but trusting submission to God’s word and purposes. Entry into God’s kingdom requires no achievement or qualification—only a willing turning and a trusting response.

These verses function as a summary and programmatic statement for the rest of Mark’s Gospel. What follows will show, in concrete scenes and encounters, what it means that God’s kingdom has come near, and what it looks like to live as people shaped by repentance and faith.

Summary & Application

Mark 1:1 - 15

Preparation for the Kingdom

The opening of Mark’s Gospel announces the beginning of a new era—the era of Christ’s victory in the world. Jesus is the long-hoped-for Messiah and King, promised by the prophets, through whom God would bring about a second Exodus and a new act of creation. What God had spoken through Israel’s Scriptures, He now brings to fulfillment in His Son. Jesus is the anointed one, the Son of God, who comes to inaugurate God’s kingdom and to give the promised Holy Spirit of the new covenant.

This passage is the beginning of “the beginning of the gospel,” and it is marked throughout by preparation. Each section builds on the last as God prepares and fulfills His saving purposes. The prophets prepared the way by announcing the coming of the Lord. John the Baptist prepared the people by calling them to repentance, summoning them to pass once more through the Jordan in readiness for God’s saving action. God also prepared His Son for this ministry—affirming Him through the heavenly voice, anointing Him with the Spirit, and testing Him in the wilderness—before He steps forward to proclaim the kingdom.

At the heart of this passage stands Jesus’ message: the time has come, and the kingdom of God has drawn near. The proper response to this moment is repentance and belief—turning from old allegiances and trusting God’s saving work now revealed in Christ. Through this response comes forgiveness, life, and restored fellowship with God.

Mark 1:1–15 thus sets the theological and narrative foundation for everything that follows. It introduces a gospel shaped by fulfillment, preparation, and divine action—a story of new creation, empowered by the Spirit, and centered on Jesus as God’s anointed King.

Ideas About Discipleship and Service

Mark 1:1–15 shows that life in God’s kingdom begins with preparation, repentance, and participation in God’s work. The good news of Jesus is not only something we believe, but something that continues to shape how we live, respond, and serve today. We live in the era of Christ’s victory over sin and death, and we are invited to live as people formed by His kingdom.

Like John the Baptist, we are called first to lives shaped by repentance and attentiveness to God, and from that place to point others to Jesus. John faithfully prepared hearts for Christ, undistracted by status, power, or comfort. His life and ministry challenge us to consider how our own lives direct attention—not to ourselves—but to Jesus.

How has your life been transformed by this good news?

How can you actively participate in pointing others to Christ?

Jesus continues to call people to repent and believe in order to experience life in God’s kingdom. Repentance involves turning away from old allegiances and patterns of life shaped by the kingdoms of this world. Belief is a posture of trust—placing our confidence in God’s word and purposes, and following Jesus as King.

Why is the kingdom of God good news to you personally?

What might repentance and belief look like in the ordinary rhythms of your daily life?

This passage also reminds us that when God begins a new work, He prepares His servants for it. Jesus Himself is affirmed by the Father, empowered by the Spirit, and then led into the wilderness. Times of testing and difficulty are not signs of God’s absence, but often part of His forming work as He prepares His people for faithful service.

In what ways might God be preparing you through His Word, repentance, or seasons of testing?

How can you be more attentive and responsive to God’s preparation in your life?

Other resources

Watch: Gospel of the Kingdom

Read: Kingdom Arrival

© 2025 Practical Bible. All rights reserved.